And to be part of this revolution, the developer goes out of its way to include wired ethernet modules or WIFI modules in its circuits. Which increases complexity, circuit size and development cost.

What if I told you that already has a built-in WIFI microcontroller? And that it fits in the palm of your hand? For just 1 US dollar?

Today I’m going to introduce you to the ESP8266 microcontroller, from Espressif. And for those of you who already program in 8Bit microcontrollers like the Atmega328 (one of the most common on Arduino) and struggle to build your code in the modic SRAM’s 2KB and Flash memory’s 32KB… The ESP8266 offers 32KB to RAM and 512KB to Flash Memory … expandable up to 4MB.

Did I get your attention? So, let’s go to a summary of the specs, provided by the manufacturer itself:

- 32-bit RISC architecture;

- 80MHz processor (can be expanded up to 160MHz);

- Operating Voltage of 3V;

- 32KB of RAM memory for instructions;

- 96KB of RAM memory for data;

- 64KB of ROM memory to boot;

- Flash memory preview by SPI (512KB to 4MB);

- Wireless 11 b/g/n standard;

- Operating modes: STA/AP/STA+AP;

- WEP, WPA, TKIP, AES security;

- Built-in TCP/IP protocol;

- QFN encapsulation with 32 pins;

- Main Peripherals: UART, GPIO, I2C, I2S, SDIO, PWM, ADC and SPI;

- Architecture with prediction of operation in energy saving

At this point you may have noticed that I stated that the ESP8266 has a 512KB Flash memory, extendable up to 4MB, but then I said that the module only provides this memory per SPI. Before explaining this, I want to draw your attention to another important point: The ESP8266 has a WIFI module inside a QFN package. WIFI is radio frequency! And how does it work without an antenna? The answer is: It doesn’t work!

The ESP8266Ex chip (this is its full name) needs an antenna to be connected to your antenna’s specific pins as well as a FLASH memory IC.

Started to get complicated? Don’t worry. With the idea of making the chip more accessible, several modules were developed that already include an antenna and a memory chip.

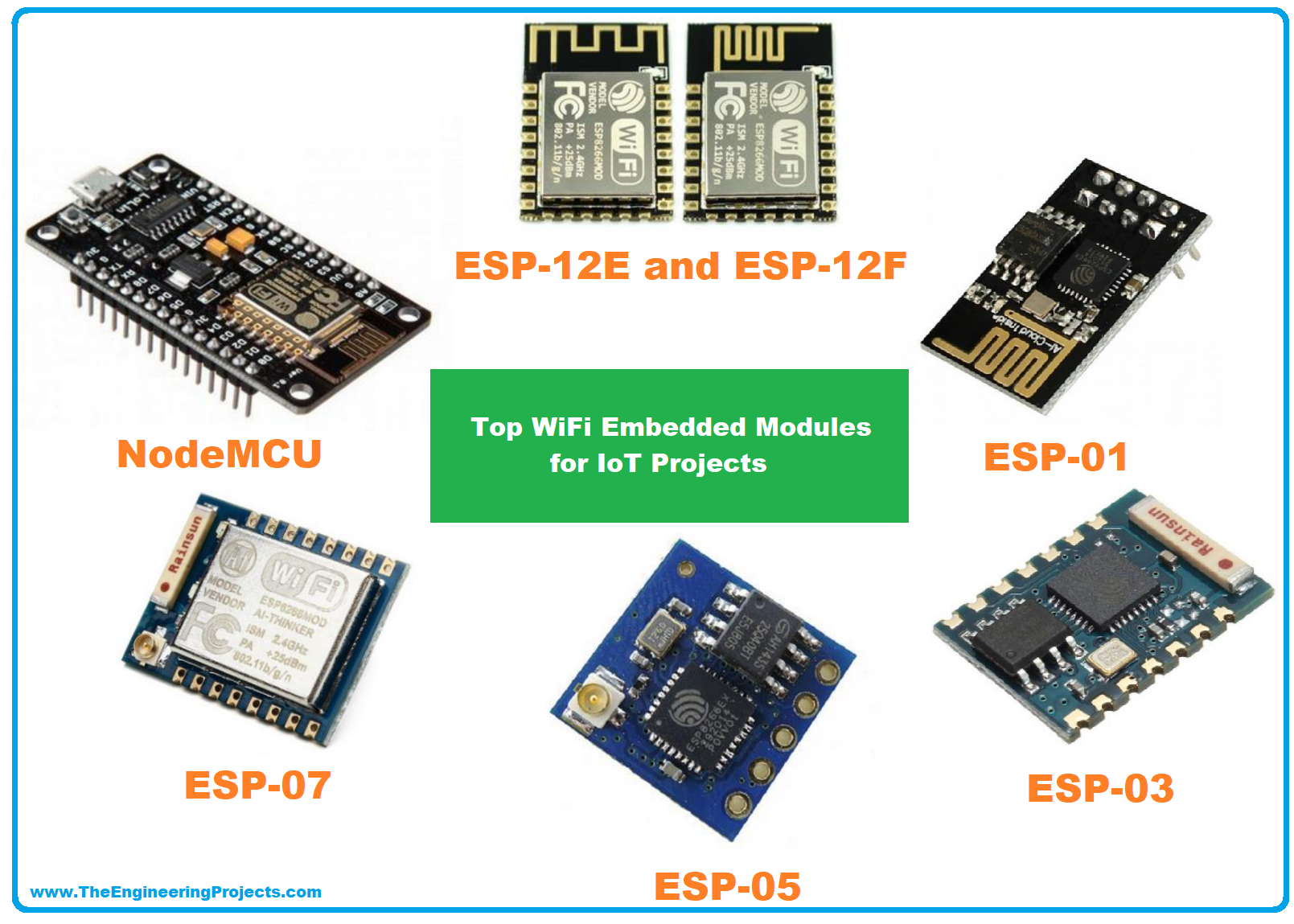

Understanding the need to include an antenna for the WIFI, a memory IC in the SPI and making pins more accessible, several manufacturers started working on ore “friendly” ESP8266’s versions. Among the best known are the ESP-01, ESP-03, ESP-05, ESP-07, ESP-12E, ESP-12F and NodeMCU. All of them have the esp8266 microcontroller in common, but they vary in size, antenna availability, memory size and pin availability. There are others, but today we’ll talk a little about them.

| Where To Buy? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Components | Distributor | Link To Buy | |

| 1 | ESP8266 | Amazon | Buy Now | |

ESP-01

It is the most common module in the ESP8266 range. It is compact (24.8 x 14.3 mm), the WIFI antenna is built in the board itself and has two GPIO pins that can be controlled according to programming. There are two significant drawbacks to this card:

- The pins are not intended for connection to a breadboard. Although they fit well, they end up shorting So, they necessarily need wires to extend the pins.

- The two available GPIOs play an important role in the board So it is necessary to pay attention to the level (high/low) when the board is initialized, or the board may mistakenly enter in programming mode. So, pins are safer operating as Outputs than as Inputs.

ESP-03

This version comes with a ceramic antenna, 7 GPIOs (two are those of the ESP-01 that require attention), a pair for UART, in size 17.4 x 12.2 mm. Smaller than 01? Yes! But that comes at a price: The encapsulation is another.

ESP-05

- No GPIOs available, it actually doesn’t even have a built-in antenna.

- This version was thought to incorporate WIFI to some other microcontroller (with the smallest possible size: 14.2 x 14.2 mm), so it has an external connector and UART pins to be manipulated by AT commands.

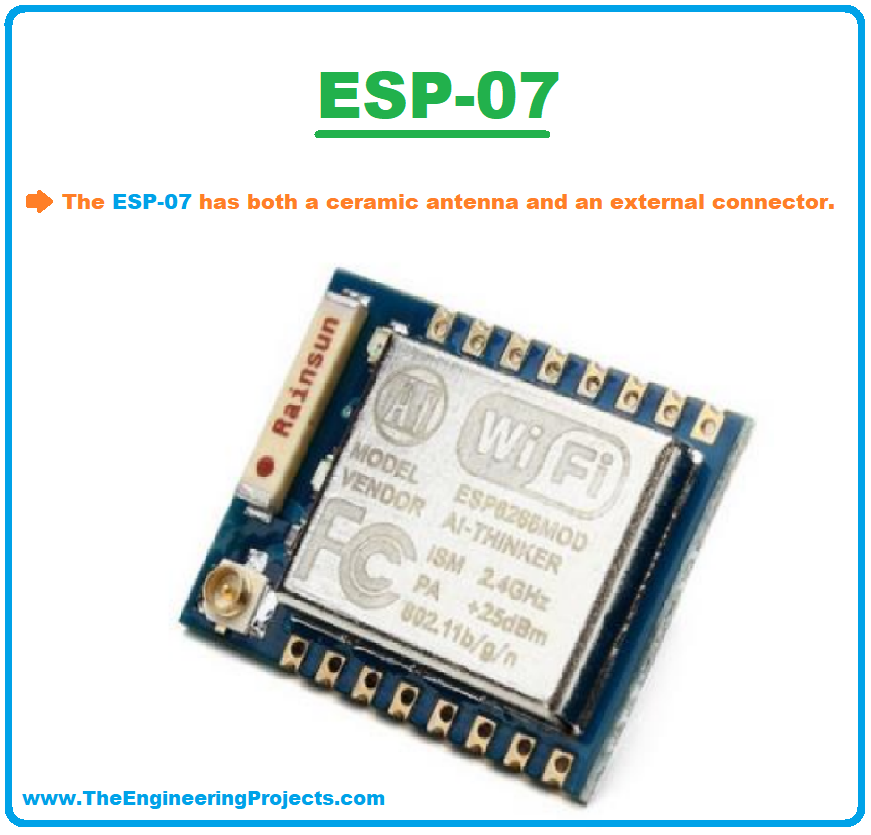

ESP-07

- The ESP-07 has both a ceramic antenna and an external connector. Looks a lot like the ESP-03, but leaves the meager analog pin available.

- In addition to incorporating a metallic cover that protects the circuit against magnetic interference.

ESP-12E and ESP-12F

Built-in antenna, 11 GPIOs, UART available, SPI available (not exactly, it’s still being used by the flash memory CI, but now you get the option to disable the memory and associate a larger one), an ADC pin (pause here to explain because it’s not that useful, The board operates with 3.3V, but the ADC is 0 – 1V. Low resolution, plus the big risk of damaging everything.).

The ESP-12E would be icing on the cake for the ESP8266’s boards, but the ESP-12F version handled an improvement in the antenna design and a little more pin protection.

NodeMCU

The NodeMCU module is to the ESP-12s as the Arduino UNO is to ATMEGA328s. A board with a protoboard compatible pinbus, all ESP-12 pins available, a 3.3V regulator to power the module (the VIN pin can receive 5V) and a UART – USB interface that turn the nodeMCU into a plug an play module.

There are versions with the ESP-12E (increasingly rare) and with the ESP-12F.

Now that we know a little more about the hardware, let’s take a look at how to program it.

There are different ways to programming the ESP8266. Different methods, different languages, among the most common, we have the ESP-IDF (manufacturer’s official. C programming) and others recommended, also, by the manufacturer: NodeMCU (Lua Script), Arduino (C++), MicroPython (you get one candy if you guess the language). It is possible to work with it in PlatformIO as well.

ESP-IDF

The ESP-IDF is the official Espressif solution. The SDK has a number of precompiled libraries and works with the Xtensa GCC compiler.

For a long time, the company has released RTOS and NON-OS versions in parallel. But since 2020 no NON-OS versions have been released (except minor bug fixes). Other modules from Espressif were born exclusive to RTOS versions, probably this was already part of the decision to bury the NON-OS. IN 2019, the company released a note stating that it would keep the main version, but that it would only operate in the correction of critical bugs. It even released some new features after that, but it doesn’t compare in quantity to the RTOS version.

This is without any doubt the most specialized tool that allows for the greatest customization at a low level. Drivers and libraries are customized for company modules. And specialization directly reflects on performance.

But the ESP-IDF lacks in complexity and size of the active community. Which ends up making the solution’s development a little slower. How does this happen? The programming is done in C- ANSI, in some cases with the directly treatment of registers, creating a more verbose code. More verbose? More chances for bugs. Also, active community is something that needs to be looked at when using any technology. Whether for creating new libraries or for sharing issues and solutions. The ESP-IDF user community exists, but it is much smaller than the others that will be presented here.

NodeMCU

The NodeMCU is an ambiguous term, it can either be used to indicate the NodeMCU module (hardware) or the NodeMCU development environment (software), both can be used together. But not necessarily. Let’s go to the software one.

The NodeMCU is a Lua-based firmware specific to the ESP8266 and uses a SPIFF (SPI Flash File System) based file system. This firmware is installed directly in FLASH memory, which allows the code’s execution in real time, without the need for compilation.

It offers a library structure for native functionality and for sensor’s integration, such DS18B20 or BME280, which make programming more dynamic.

The NodeMCU has been popular for quite some time. But it has three serious problems that have started to reduce its use.

- The Firmware NodeMCU, installed in FLASH, takes up a lot of Especially if the full version is included.

- It was developed based on the NON-OS version, so, firmware bugs started to get more complex to

- The memory management is quite complex in some cases. Because it didn’t compile, some memory overflow issues could only be noticed at runtime. (This was the reason I stopped using this method).

Arduino

The Arduino platform, undoubtedly the best known in the world when it comes to microcontrollers, is also on the manufacturer’s list of nominees.

The Arduino was built as software-hardware relationship that makes microcontroller’s development more accessible to non-specialists. The hardware complexity was minimal (in some cases none) and the software started to be treated in a high-level language (C++), allowing even object orientation.

Because it is so accessible, some members of the software’s community have started to be collaborators in building libraries (Only to control LCD displays, I know four), some sensor’s manufacturers offer official versions as well. Constantly updated material. Etc. Etc.

The Arduino architecture started with the Arduino Uno board (which uses an ATMEGA328), expanded support to other boards and… for some time now, it has support for ESP8266 in different modalities. There is good compatibility with standard Arduino libraries and it has its own.

MicroPython

I Don’t know the MicroPython in practice (yet), but as the name advertises, it allows programming in Python. Like NodeMcu, it deploys a firmware to FLASH memory and has well- defined libraries for hardware usage.

The space occupied in Flash is well optimized (not even compared to NodeMCU chaos). It seams to have a very active community. As for programming complexity I don’t have much information. But if you program in Python, I think it’s worth the experience.

PlatformIO

The PlatformIO is not really a development platform, but it allows an integration with other platforms to simulate the board. If you don’t have an ESP8266 on dang yet, it might be a good choice for your first steps.

However, there is a natural limitation when simulating a module whose flagship is WIFI.

Don’t you know where to start?

Personally, I think that the Arduino environment is perfect for prototyping. It’s easy to get results pretty quickly to validate a proof of concept. But in some cases you can go beyond that. If your project doesn’t demand maximum performance from the ESP8266, even the production version can be built here.

For a project that requires a lot of hardware precision, I don’t recommend intermediaries. Nothing will perform better than IDF.

For educational purposes, our next articles will use the NodeMCU board programmed on the Arduino platform.